Jittrbug.net

- Home

- News

- Blog

- Video Trailer

- Screenplay

- Jitterbug! Songwriting Team & Creative Directors

- Music

- The Story

- The Dramaturgy Behind The Story

- Jitterbug Dance Origins

- Get Your Choreography Right Here!

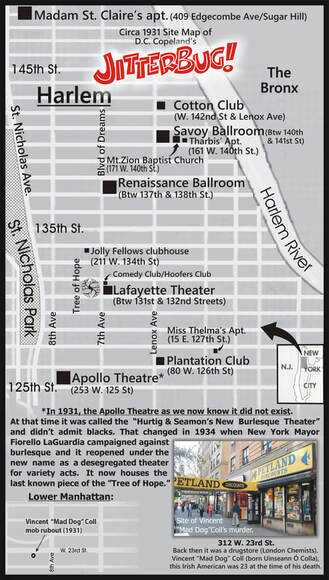

- Map of historic locations in play

- Playwright

- The Director

- The Choreographer

- Jitterbug! NYC Pixs

- Emerging Artists Theatre (EAT)

- Tada! Youth Theatre

- National Black Theatre

- The National Black Theatre Cast

- Follow-up to the NBT radio reading

- Books

- Educator Resources

- Royalties

- Everything Jitterbug! Store

- Gallery

- Contact

How it all began...

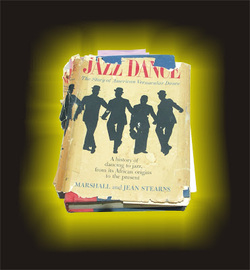

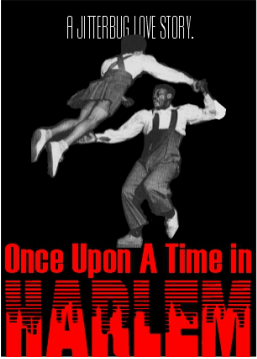

It all began with a book called Jazz Dance by Marshall and Jean Stearns. It explores what they considered to be one of America's great gifts to the world, what they called "American Vernacular Dance." They traced the jitterbug and tap dancing in particular as an expression of what the body hears and feels when listening to jazz. Jazz, of course, owes everything to African rhythms and improvisation. Since I was taking jazz dance and tap classes at that time, I was intrigued with the Stearns' contention that tap dancing was "America's only true indigenous art form." They did this by connecting the dots between poor African Americans and newly arrived Irish immigrants rubbing shoulders together in Harlem and New York City at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Basically African Americans added jazz rhythms to the Irish jig. To prove their point, they interviewed over 200 people from "back in the day" who actually were there when dance and music was transforming itself into something that "swings." Many of these pioneers of vernacular dance had already died before the interviews began around the early to mid-sixties but enough were still around to fill the book with the most amazing stories. It was these stories that inspired me to write Once Upon A Time In Harlem: A Jitterbug Romance as a screenplay and then a play. I wrote a truncated "radio"/reading version of the play to make it more affordable and easier to produce. This version is perfect for high school and college classrooms. And, of course, after all of these iterations, I recently changed its name to "Jitterbug!"

Here's a rare TV interview of my hero Marshall Stearns who made an appearance on the Playboy magazine 1960 talk show "Playboy Penthouse." It features early turn-of-the-century bonafide American vernacular dances as well as many swing steps demonstrated by legendary Lindy and Jitterbug dancers Al Minns and Leon James who Stearns describes as "Kings of the Savoy Ballroom" some thirty years after the fact. Consider this a one-stop-shop for period Lindy and Jitterbug dance moves as Stearns calls out the steps and they show the world how they're done.

Here's a rare TV interview of my hero Marshall Stearns who made an appearance on the Playboy magazine 1960 talk show "Playboy Penthouse." It features early turn-of-the-century bonafide American vernacular dances as well as many swing steps demonstrated by legendary Lindy and Jitterbug dancers Al Minns and Leon James who Stearns describes as "Kings of the Savoy Ballroom" some thirty years after the fact. Consider this a one-stop-shop for period Lindy and Jitterbug dance moves as Stearns calls out the steps and they show the world how they're done.

Everything old is new again.

B-Boys doing their thang May 12, 1894 from The Passing Show revue at the Casino Theater in NYC, Edison Kinetoscope Company. This film is listed in the back of Jazz Dance, a book I first read in the early 70's. I had to wait until YouTube made the scene to see it. BTW, The Passing Show was the first American revue to use the term, although they spelled it "review." Aside from its bad NYT review ("the show contained elements of amusement... But there were great wearisome spaces of emptiness..."), apparently this short footage is the only thing that survived the show and the theater which was torn down in 1930.

B-Boys doing their thang May 12, 1894 from The Passing Show revue at the Casino Theater in NYC, Edison Kinetoscope Company. This film is listed in the back of Jazz Dance, a book I first read in the early 70's. I had to wait until YouTube made the scene to see it. BTW, The Passing Show was the first American revue to use the term, although they spelled it "review." Aside from its bad NYT review ("the show contained elements of amusement... But there were great wearisome spaces of emptiness..."), apparently this short footage is the only thing that survived the show and the theater which was torn down in 1930.

Digging Deeper...

Please click to enlarge.

Once I started learning about the legendary people and places of Harlem for my play, it became important for me to keep track of them. I did this through index cards and by creating a map of Harlem, circa 1931.

In retrospect, I wish I had included Manhattan in the map to pinpoint the locations of the gangland murders that are relevant to the play's story. Those actual addresses however are found in the play (as is the above map in the playbook). This is a process I used to keep the fictional aspects of the story plausible. As an example, when my main characters Billy Rhythm and Tharbis Jefferson are walking down Lenox Avenue in Harlem and see white gangsters from the Cotton Club taking hatchets and sledge hammers to the rival Plantation Club and then throwing the debris into a bonfire in the middle of the street, I wanted to see if it was plausible for them to have walked to the Harlem River within a reasonable amount of time for the next scene. I discovered it was. My research also found a secondary source-- a newspaper article written about that incident recalled in a book (my first source)-- that backs up the story. As an added bonus, that article gives a voice to the African American perspective of what happened, revealing an underlying resentment to the white gangsters and others who came into their community and opened businesses that would bar Harlemites at the door. That info is included in the annotations found in the playbook. The annotations are there for the actors and the readers to help them better understand the time, place and psychological make-up of the characters in the play. Like the final sentence on the back cover of the playbook, it helps remind everyone that "it all happened in an almost forgotten time in America's most mythic city: Harlem."

In retrospect, I wish I had included Manhattan in the map to pinpoint the locations of the gangland murders that are relevant to the play's story. Those actual addresses however are found in the play (as is the above map in the playbook). This is a process I used to keep the fictional aspects of the story plausible. As an example, when my main characters Billy Rhythm and Tharbis Jefferson are walking down Lenox Avenue in Harlem and see white gangsters from the Cotton Club taking hatchets and sledge hammers to the rival Plantation Club and then throwing the debris into a bonfire in the middle of the street, I wanted to see if it was plausible for them to have walked to the Harlem River within a reasonable amount of time for the next scene. I discovered it was. My research also found a secondary source-- a newspaper article written about that incident recalled in a book (my first source)-- that backs up the story. As an added bonus, that article gives a voice to the African American perspective of what happened, revealing an underlying resentment to the white gangsters and others who came into their community and opened businesses that would bar Harlemites at the door. That info is included in the annotations found in the playbook. The annotations are there for the actors and the readers to help them better understand the time, place and psychological make-up of the characters in the play. Like the final sentence on the back cover of the playbook, it helps remind everyone that "it all happened in an almost forgotten time in America's most mythic city: Harlem."

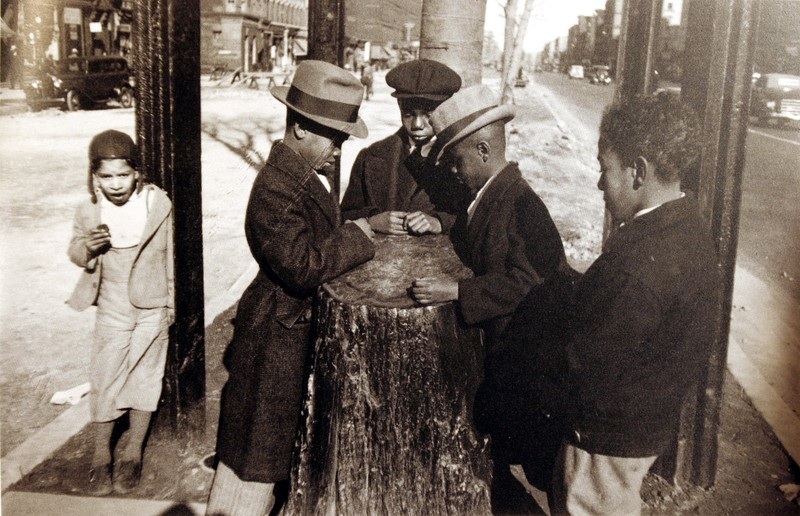

The Tree of Hope and the Lafayette Theatre

That's the Tree of Hope in front of the legendary Lafayette Theater up on 7th Ave at 132nd Street in Harlem. On the right is the equally legendary Connie's Inn.

This is what happened to the tree.

Please click image to enlarge.

That plaque in the photo on the left was put there in 1941 by Bill "Bojangles" Robinson (with the assistance of NYC mayor Fiorello LaGuardia) to mark the spot where the tree had been before it was chopped down to make room for the expansion of 7th Ave (the "Boulevard of Dreams") in 1934. Much of it was sold for firewood but some of it was sold as souvenirs to people who believed it would bring them luck.

Say what? Tradition had it that out-of-work performers would rub the tree for good luck in landing a gig. Everybody who was anybody at the beginning of their careers stopped by to rub the tree with this simple request, "Hope to get a gig." This included future luminaries such as Ethel Waters, Fletcher Henderson, and Eubie Blake. That's what my main character Billy Rhythm does when he returns to Harlem in my play Once Upon A Time In Harlem: A Jitterbug Romance.

Say what? Tradition had it that out-of-work performers would rub the tree for good luck in landing a gig. Everybody who was anybody at the beginning of their careers stopped by to rub the tree with this simple request, "Hope to get a gig." This included future luminaries such as Ethel Waters, Fletcher Henderson, and Eubie Blake. That's what my main character Billy Rhythm does when he returns to Harlem in my play Once Upon A Time In Harlem: A Jitterbug Romance.

Watercolor rendering of the Lafayette

interior.

Watercolor rendering of the Lafayette

interior.

As for the 1,223-seat Lafayette Theater, it was the first theater in NYC to desegregate when it opened in 1912 and remained that way for a very long time before all the NYC theaters desegregated. This meant that Harlemites could finally sit in the orchestra instead of just the balcony (disparagingly labeled "nigger heaven")-- the only seats they could sit in any NYC theater-- if they were allowed to buy tickets in the first place. Known as "the House Beautiful" because of its ornate Renaissance Revival architecture and interior, it was home to the Lafayette Players, one of the first African-American professional theatre troupes (1916).

Please click image to enlarge.

Please click image to enlarge.

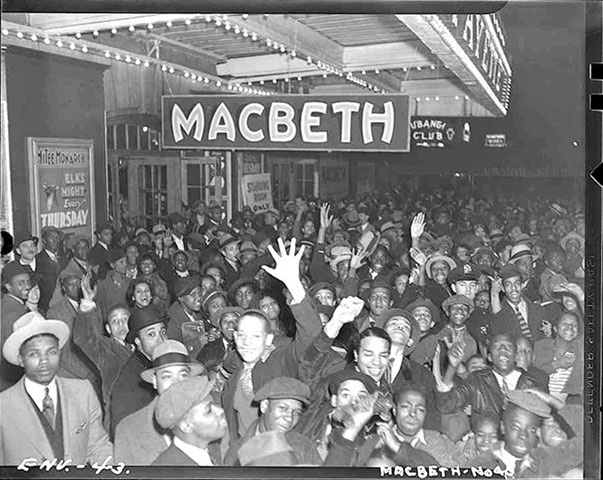

In 1936, 20-year-old Orson Welles used the theater in a reimagined Shakespeare's Macbeth set in Haiti. Because of its African American cast (the Federal Theatre Project's Negro Unit) and setting, it was labeled "Voodoo Macbeth." It sold out for 10-weeks before moving to Broadway followed by a national tour.

It was said "10,000 people stood as close as they could to the theatre," jamming 7th Avenue for 10-blocks and "halting northbound traffic for more than an hour." The New York World Telegram reported that an integrated group of "Harlemites in ermine, orchids, and gardenias, Broadwayites in mufti" had filled every seat. Scalpers were getting $3.00 for a pair of 40-cent tickets. The New York Times reported the audience was "enthusiastic and noisy" and encouraged Macbeth's soliloquies.

In between performances by the Lafayette Players and such, the Lafayette showcased acts of all types and in this regard was the precursor of the Apollo Theatre (which until 1934 was called the "Hurtig and Seamon's New Burlesque Theater" and did not admit blacks. That changed in 1934 when Fiorello LaGuardia campaigned for mayor against burlesque and it reopened as a desegregated theatre with a new name: the 125th Street Apollo). Today the Apollo Theatre is home to what may be the only piece of the original "Tree of Hope" thanks to an enterprising visionary and performer named Ralph Cooper, Jr. He bought a 12" x 18" piece and brought it back to his dressing room at the Apollo where he had it sanded, shellacked and mounted to an iconic column. That night just before the first "Amateur Night at the Apollo" show began, it was placed stage right just outside the curtain so the audience could see it. Since then it's become de rigueur to touch the Tree of Hope for all Wednesday Amateur Night performers.

The Fate of the Lafayette

Please click image to enlarge.

As for the Lafayette's fate, unlike so many of the famous landmarks of old Harlem-- the Cotton Club, the Savoy Ballroom, and more-- it's still with us but in 1990 it was "reimagined" as the Williams Institute C.M.E. Baptist Church to make it more "church-like." That's too bad because I think God would have been comfortable in the building as it was. Unfortunately, preservationists were too late and this is what we got, a very forbidding and unfriendly structure that appears to be barricading itself against the temptations of the outside world just beyond those massive walls and doors:

To quote one of my favorite Harlem Renaissance poets, Countee Cullen--who apparently no one at the church was reading at the time of the transformation:

To quote one of my favorite Harlem Renaissance poets, Countee Cullen--who apparently no one at the church was reading at the time of the transformation:

“And what would I do in heaven, pray,

Me with my dancing feet,

And limbs like apple boughs that sway

When the gusty rain winds beat?

And how would I thrive in a Perfect place...

Where dancing be sin,

With not a man to love my face

Nor an arm to hold me in?”

--from She of the Dancing Feet Sings, 1926

Me with my dancing feet,

And limbs like apple boughs that sway

When the gusty rain winds beat?

And how would I thrive in a Perfect place...

Where dancing be sin,

With not a man to love my face

Nor an arm to hold me in?”

--from She of the Dancing Feet Sings, 1926

I'm sure souls are being saved behind those closed doors, but what a loss for Harlem in terms of its history. I wonder what would have happened if the church had left the building alone. Do you think people would be lining up out front like they did back in the day for Macbeth; banging on the doors in hopes of getting in to get saved and closer to Jesus?

The Lafayette, Harlem

The Lafayette, Harlem

Update Thanksgiving 2013: The church/Lafayette Theater and the block they stood on are being razed for a new 8-story rental apartment building (115 apartments with 1/5 slotted for lower-income families) that will include 19,000sf for the church, a new garage, and new stores. Wonder if anyone lobbied for inclusion of a new, smaller theater in the mix? Guess not.

The Cotton Club & Cab Calloway

When I started writing Once Upon A Time In Harlem: A Jitterbug Romance, I knew I wanted to include the Cotton Club but I couldn't decide on a year-- until I read Cab Calloway's autobiography, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, and then it became a no-brainer: 1931, the year the Cotton Club built a show around him called Rhyth-mania. This was two years after replacing Duke Ellington and his band at the club when they went to Hollywood to make their first movie, an all-African American short called Black and Tan (1929). Cab was just 22-years old when he took up the Cotton Club baton. He got the gig thanks to Irving Mills, a white music agent and producer who broke down color barriers when he brought black and white bands together to rehearse and to make music for his company EMI. What I didn't know at that time when I started writing was just how original and dynamic a performer Calloway was. This was 30-years before YouTube.com where you can easily click onto a vintage piece of film from that by-gone era and see the man for yourself. As for me, seeing the video reinforces my conviction that I made the right decision. Aside from being the right age-- most of my characters are in their twenties since they're members of of a legendary gang called the Jolly Fellows-- he and my main characters Billy Rhythm and Tharbis Jefferson tap the zeitgeist of that era. Although the Duke was a genius, he was too intellectual and laid back for what I was trying to convey. Cab fulfilled that mission and more-- his Hep-Cat Dictionary helped me nail down the jive from that period.

The first thing that strikes you when watching the video is how handsome and charismatic Calloway was. The second thing, no one ever conducted a band like he did. He was a force to be reckoned with, channeling a daemon that filled his body and soul with uninhibited abandon. The video above shows Cab when he was about 26-years-old when he made a short for Irving Mills called Cab Calloway's Hi-De-Ho to promote his new record. Since it's nearly 80-years-old, it can be forgiven for its lameness and cliches but it does have a surreal element that makes it worth watching until the end. And although parts of it takes place at the Cotton Club, I doubt if it was actually filmed there (the club was much more claustrophobic inducing but it does accurately depict what a "high-yeller" Cotton Club "Tall, Tan & Terrific" showgirl looked like). Still, it gives those who have never seen Cab doing his thing a chance to see what "all the hubbub" was about back then surrounding this young band leader working out of a small mob-ran club in Harlem. Thanks to nightly nationwide live radio broadcasts, Cab and the Club's young Jewish songwriting team of Harold Arlen-- who would later write the music for The Wizard of Oz-- and Ted Koehler were selling records "like hotcakes" and transforming America and the world with the new sound of "Swing."

The first thing that strikes you when watching the video is how handsome and charismatic Calloway was. The second thing, no one ever conducted a band like he did. He was a force to be reckoned with, channeling a daemon that filled his body and soul with uninhibited abandon. The video above shows Cab when he was about 26-years-old when he made a short for Irving Mills called Cab Calloway's Hi-De-Ho to promote his new record. Since it's nearly 80-years-old, it can be forgiven for its lameness and cliches but it does have a surreal element that makes it worth watching until the end. And although parts of it takes place at the Cotton Club, I doubt if it was actually filmed there (the club was much more claustrophobic inducing but it does accurately depict what a "high-yeller" Cotton Club "Tall, Tan & Terrific" showgirl looked like). Still, it gives those who have never seen Cab doing his thing a chance to see what "all the hubbub" was about back then surrounding this young band leader working out of a small mob-ran club in Harlem. Thanks to nightly nationwide live radio broadcasts, Cab and the Club's young Jewish songwriting team of Harold Arlen-- who would later write the music for The Wizard of Oz-- and Ted Koehler were selling records "like hotcakes" and transforming America and the world with the new sound of "Swing."

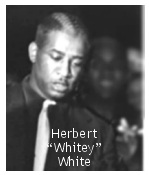

The Jolly Fellows & Herbert White

Despite Jim Crow laws, Prohibition and the Depression, something magical was happening in Harlem in the 1930's and it was more than just the intellectual rise of the Harlem Renaissance. Something wonderful was going on below the radar of the intelligentsia. A street gang had become without any plan of its own the protector and champion of American "vernacular dancing," i.e., tap and swing.

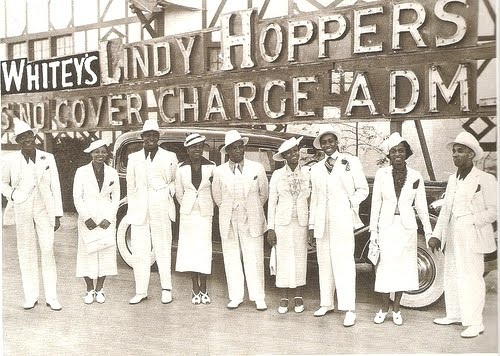

The Jolly Fellows, was one of the toughest of a dozen "secret" street gangs in Harlem, i.e., they didn't emblazon the backs of their jackets with the names of their gang. But that's not to say you couldn't spot a Jolly Fellow on the streets of Harlem. Thanks to Herbert "Whitey" White, who organized the gang in 1923, he instilled in his young members that they must at all times dress well and smell good.Described as a cross between a "penny-pinching Robin Hood and a hip Father Flannigan," White was a one-time prize fighter and a sergeant in World War I. He was also as much as 20-years older than most of the gang members who were for the most part "twenty-somethings" by the time my play takes place. To get accepted into the club, one of the initiation rights included walking into a store, punching the store owner and waiting to see what happens. Sometimes you went to jail, sometimes not. By the 1930's, membership had risen to over 600 (and I would suspect there were an equal number of store owners with black eyes, broken jaws, and concussions).

The Jolly Fellows, was one of the toughest of a dozen "secret" street gangs in Harlem, i.e., they didn't emblazon the backs of their jackets with the names of their gang. But that's not to say you couldn't spot a Jolly Fellow on the streets of Harlem. Thanks to Herbert "Whitey" White, who organized the gang in 1923, he instilled in his young members that they must at all times dress well and smell good.Described as a cross between a "penny-pinching Robin Hood and a hip Father Flannigan," White was a one-time prize fighter and a sergeant in World War I. He was also as much as 20-years older than most of the gang members who were for the most part "twenty-somethings" by the time my play takes place. To get accepted into the club, one of the initiation rights included walking into a store, punching the store owner and waiting to see what happens. Sometimes you went to jail, sometimes not. By the 1930's, membership had risen to over 600 (and I would suspect there were an equal number of store owners with black eyes, broken jaws, and concussions).

Cat's Corner and Chesterfields

Please click image to enlarge.

White wasn't a great dancer-- he was better at banging heads, intimidation, and entrepreneurship-- but because he loved great dancing, the Jolly Fellows (and their women's auxiliary the Jolly Flapperettes) became known as the dancer's gang. As the head bouncer at the world-famous Savoy Ballroom (a block long with a double-bandstand and a sprung wooden floor that could hold 5,000 people), his gang could dance as long as they wanted on a certain part of the floor called "Cats Corner." No one else could dance there. If for some reason a couple inadvertently spent too much time "in the paint," it could mean a good beating (usually given through choreographed Charleston kicks). When it came to defending one's turf or a gang member's honor, it was done in the highest of the GQ style popularized by Edward G Robinson's gangster flicks: Jolly Fellows went to a fight wearing gloves, tight Chesterfields (see picture), and derbies. As a side note, besides not tolerating "coarse language," White also required that women were to be treated with "unfailing courtesy."

The Hoofers' Club

To get into the Hoofers' Club, you first had to enter the Comedy Club next door to the Lafayette Theatre on Seventh Ave ("Boulevard of Dreams") between 131st and 132nd Streets. The Comedy Club was a small storefront for a speakeasy and gambling house. It was also a favorite Jolly Fellows hangout. In an even smaller backroom, was the Hoofers' Club. It was big enough to hold an old, beat-up upright piano and a bench. The splintered wood floor is where men practiced tap dancing and new steps and routines came to life. Jazz Dance says this small backroom was the "unacknowledged headquarters for tap dancing" for nearly 40-years. Everyone who was anyone stopped by to dance including Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, the "Mayor of Harlem." There were only two rules: don't bother guys like Bojangles and John Bubbles with questions about how to do a certain step when they came in to dance and most importantly, don't copy another's steps. "Thou Shalt Not Copy Another's Steps-- Exactly" was the unwritten law. You could imitate anybody inside the "club"-- it was taken as a compliment-- but you couldn't do it professionally, i.e., in public and for pay. It's said when a new act opened at the Lafayette or the Lincoln, as soon as the doors opened, dancers rushed down to the first rows and "watched you like hawks and if you used any of their pet steps, they just stood right up in the theatre and told everybody about it at the top of their voices."

The Jitterbug

By the mid-30's Herbert White began using his entrepreneurial skills to tap into America's growing passion for swing dancing. The earliest version was revealed to the world in June of 1928 through a Jolly Fellow when a Fox Movietone News reporter asked legendary gang member-cum-dancer George "Shorty" Snowden what he was doing with his feet? Snowden never stopped dancing when he replied, "The Lindy." Credited with adding the "breakaway" to the dance so he could improvise steps, Snowden was preparing the world for the dance that was yet to come: the Jitterbug. It was born at the Savoy Ballroom because of the Jolly Fellows. By the time the dance got airborne through "air-steps," it had become known as the "Jitterbug," thanks to Herbert White and Cab Calloway's 1934 recording, Call of the Jitter Bug, which used the word in its earliest iteration as a description of someone with the "delirium tremors" from drinking too much booze. The song appears at the end of the short below:

If you'd like to be a jitter bug,

First thing you must do is get a jug,

Put whiskey, wine and gin within,

And shake it all up and then begin.

Grab a cup and start to toss,

You are drinking jitter sauce!

Don't you worry, you just mug,

And then you'll be a jitter bug!

First thing you must do is get a jug,

Put whiskey, wine and gin within,

And shake it all up and then begin.

Grab a cup and start to toss,

You are drinking jitter sauce!

Don't you worry, you just mug,

And then you'll be a jitter bug!

At the height of the dance's popularity, White was managing as many as seventy dancers and a dozen dance troupes with names like The Savoy Hoppers, The Jive-A-Dears, and his most famous, Whitey's Lindy Hoppers. That troupe (which at one time included Shorty George and his dancing partner Big Bea) toured the world including Paris with a gig at the Moulin Rouge. It also appeared in the Marx Bros movie A Day at the Races (1937) and Hellzapoppin'(1941).

By the time White died in the 1940's he was a rich man and the Jitterbug had conquered the world-- if only for a short time. By the time I took my play to Harlem this March for a reading at the National Black Theatre, 80+ years after the fact proved problematic: finding just one African-American couple who could dance the Lindy (much less the amplified Jitterbug) was nearly impossible. By the early 60's dances like The Stroll and especially the Twist finally took Shorty Snowden's "breakaway" (whether he was aware of it or not, he was reaching back to his African roots where partner dancing was basically unheard of) and made it permanent. Now it appears the only people dancing the Jitterbug today are white people, that they have in fact co-opted the dance born in Harlem. This "retro swing" movement began in the early 80's and can be traced to California and disaffected punk rockers who were exploring swing music. Still if you search hard enough you will find people like Ryan Francois (a black Brit dancing with a white partner) and, as far as I can tell, one of the few African American groups still carrying on the tradition like The Harlem Swing Dance Society-- but who have few, if any, young members (it's interesting to note that a member of that group offers up this explanation for its skewed older demographic: when the great Harlem ballrooms finally closed, no one passed on the dance to their children). Of course, it also had a lot to do with the decline in swing bands and the advent of rock and the natural tendency of the next generation to want to "break away" from whatever it was their parents embraced.

As for Mr. Francois, this dance comes closest to the one I wrote for my main protagonist. Billy Rhythm, dancing under a Harlem street lamp, uses only his feet and body to express his love for Tharbis Jefferson as she leans out of her second story tenement window. When watching it, try to imagine just one guy dancing in this "Romeo and Juliet" moment because what I was trying to capture was the magic of Gene Kelly's memorable Singing in the Rain dance number and reimagining it without singing or music (or rain); stripping it down to its joyful heartfelt African influenced American core: tap dancing.

As for Mr. Francois, this dance comes closest to the one I wrote for my main protagonist. Billy Rhythm, dancing under a Harlem street lamp, uses only his feet and body to express his love for Tharbis Jefferson as she leans out of her second story tenement window. When watching it, try to imagine just one guy dancing in this "Romeo and Juliet" moment because what I was trying to capture was the magic of Gene Kelly's memorable Singing in the Rain dance number and reimagining it without singing or music (or rain); stripping it down to its joyful heartfelt African influenced American core: tap dancing.

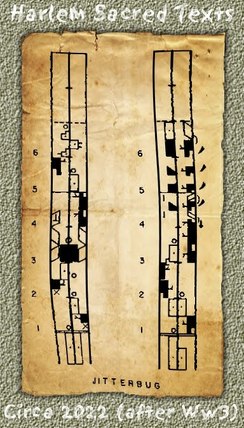

Harlem's Sacred Texts & "The Unified Field Siri"

At the end of the Third World War, lightning was the only source of electricity. Cities were in ruins and mankind had once again become hunters and gathers. By the end of the first generation to survive the war, organized religion had bit the dust too and been replaced with new superstitions to comfort and explain the new reality. Hardly anyone read anymore and, most telling, sing. Smiles were seldom seen and a spiritual depression settled across the land.

Cosmically speaking, Earthlings were no fun anymore—except for a small group of people up in Harlem who were ancestors of the first generation survivors. They called themselves "Baptists" after the name on a sign they uncovered during the excavation of a large building. As they continued to dig, more things of an ancient past were found including a small scrap of yellowed paper that would become part of their “sacred texts.” It contained mysterious symbols no one could interpret and only one word: Jitterbug.

Another generation would have to live and die before the symbols could be understood. Thanks to one man’s curiosity which only grew deeper with each layer of the past he uncovered at the bottom of the building, the world would once again experience the joys of being human. That man would become known as “Jaz The Baptist.” He discovered that the building had once been a “church” for a forgotten religion which had been built upon an earlier structure called a “Lafayette.” In the deepest strata, objects were found that when blown or beaten would create sounds unlike anything heard following the war.

Jaz The Baptist also uncovered thousands of sheets of paper with more indecipherable markings accompanied with words like swinging, jazz, and up tempo. During that dig, they also found a book written by some ancient alchemist named “Laban” with more of the sacred markings above words like “Trucking,” “Suzy-Q,” and “Shorty George.” The pages were so old just handling them as gently as possible wasn’t enough to keep them from disintegrating in one’s hands. So to preserve them, the pages were carved into a large slab of broken concrete which, over time, became known as the “Lafayette Stone.” That book led to the rediscovery of “dancing” because “Laban The Great” (as he would become known) had devised a system of interchangeable symbols that could describe every dance known to man and those that were yet to come. Unfortunately they needed something called “music” to work. It was Jaz The Baptist who made the connection between the mechanical sound making devices and the thousands of sheets of paper with the strange markings and the symbols on the Lafayette Stone. This discovery now known as “The Unified Field Siri,” with siri, a South Indian Tamil word meaning “to smile” chosen to describe the reaction the interaction of music and dance brings to mankind.* In order to spread this wonderful new discovery as far and wide and as quickly as possible Jaz the Baptist recruited hundreds of followers of this new movement to transcribe the sacred texts. The Lafayettes, as these scribes would become known, worked tirelessly day and night to get “the Word” out and, thanks to their effort, music— specifically swing music— the Jitterbug, smiles, and laughter were returned to the world.

*That dig also unearthed a dictionary.

Cosmically speaking, Earthlings were no fun anymore—except for a small group of people up in Harlem who were ancestors of the first generation survivors. They called themselves "Baptists" after the name on a sign they uncovered during the excavation of a large building. As they continued to dig, more things of an ancient past were found including a small scrap of yellowed paper that would become part of their “sacred texts.” It contained mysterious symbols no one could interpret and only one word: Jitterbug.

Another generation would have to live and die before the symbols could be understood. Thanks to one man’s curiosity which only grew deeper with each layer of the past he uncovered at the bottom of the building, the world would once again experience the joys of being human. That man would become known as “Jaz The Baptist.” He discovered that the building had once been a “church” for a forgotten religion which had been built upon an earlier structure called a “Lafayette.” In the deepest strata, objects were found that when blown or beaten would create sounds unlike anything heard following the war.

Jaz The Baptist also uncovered thousands of sheets of paper with more indecipherable markings accompanied with words like swinging, jazz, and up tempo. During that dig, they also found a book written by some ancient alchemist named “Laban” with more of the sacred markings above words like “Trucking,” “Suzy-Q,” and “Shorty George.” The pages were so old just handling them as gently as possible wasn’t enough to keep them from disintegrating in one’s hands. So to preserve them, the pages were carved into a large slab of broken concrete which, over time, became known as the “Lafayette Stone.” That book led to the rediscovery of “dancing” because “Laban The Great” (as he would become known) had devised a system of interchangeable symbols that could describe every dance known to man and those that were yet to come. Unfortunately they needed something called “music” to work. It was Jaz The Baptist who made the connection between the mechanical sound making devices and the thousands of sheets of paper with the strange markings and the symbols on the Lafayette Stone. This discovery now known as “The Unified Field Siri,” with siri, a South Indian Tamil word meaning “to smile” chosen to describe the reaction the interaction of music and dance brings to mankind.* In order to spread this wonderful new discovery as far and wide and as quickly as possible Jaz the Baptist recruited hundreds of followers of this new movement to transcribe the sacred texts. The Lafayettes, as these scribes would become known, worked tirelessly day and night to get “the Word” out and, thanks to their effort, music— specifically swing music— the Jitterbug, smiles, and laughter were returned to the world.

*That dig also unearthed a dictionary.

|

|